It was a Beneteau Oceanis 381 with a layout similar to last years except below deck was a flip flop opposite. Only one quarter berth which was a full. Larger V berth forward. Diesel forced air heater which we used a couple of times. Chilly until noon. Sunny afternoons. Never rained. The AYC yachts are individually owned and you could tell that our boat was looked after.

Big galley with two refrigerators. Propane BBQ. Galley stove oven had a broiler.

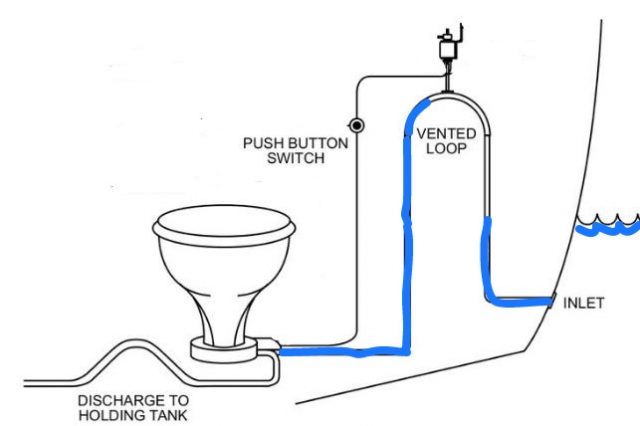

Smaller Lav space (as if that was even possible). The holding tank was a mere 15 !! gallons and with strict eco regs in US waters that meant we really had to watch it. I had the pleasure of pumping it out twice. Well, pump-outs are encouraged by being free anyway.

We anchored out once. Picked up a ball at two other stops. BTW, you taught Spencer well on the fore-deck He was invaluable. Leah was a complete noobe on day one but by mid week she had it down and by voyage end had the sailing bug. Stayed on a linear mooring one night and one night on a dock. Also, we had to put our own boat in its slip back in Anacortes. No such thing as a marina skipper.

Cleared Canadian / US customs which was good experience. Navigation fairly easy with the GPS tracking and land ho. Fewer visual cues on the long sail to and from Victoria in which case it was GPS track and DR

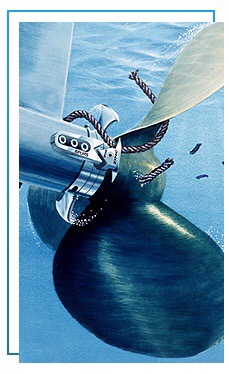

I kept a watchful eye on tides and currents. We traversed a few tidal current rips but those were a non event. We had to be careful for floating logs. We saw several. Man that would have made a big noise to collide. Remind me not to sail there at night. Big container ships in the lanes too. The most current was 2.5 knots which didn’t last long and luckily was going our way.

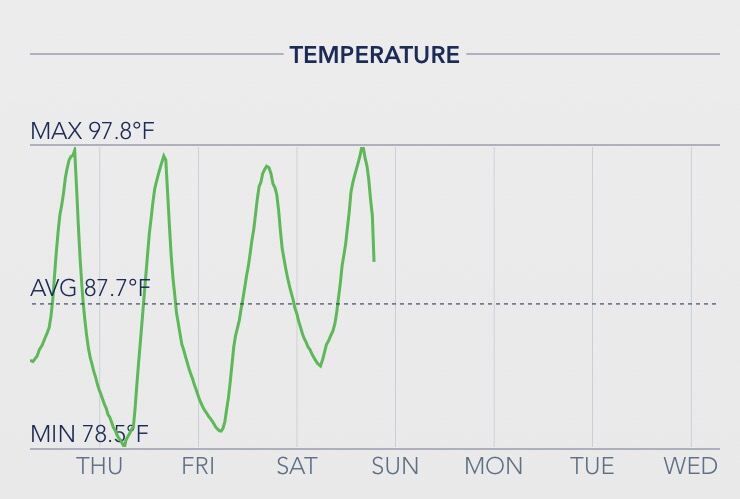

The most wind that we saw was 16 knots at which full sail was slightly over powered close hauled. The main sail could be furled into the mast. Very trick. 1 to 2 foot wind waves at times. For the most part the wind was 6 to 10 knots. The ride was always good. Our charter had Radar with AIS if we’d have been caught out by fog but we were only concerned once and it turned out not to be a factor.

Like Father like son, Spencer almost did an endo off of the transom but fell into the dinghy instead. Whew!

53 degrees. I was concerned about going overboard while underway and nobody noticing right away. That would have been bad scene.

v1.5

v1.5