WW II

Henrik Walter Strombotne

Dad’s brother, Chris, took up flying in Cheyenne, Wyoming and in fact made the local newspaper there when his Luscombe trainer lost a wheel (leaving only one) to make a safe emergency landing return. When hostilities broke out and the USA went to war, Chris endeavored to do his part. He received an ‘advanced commission’ with the US NAVY as an Ensign meaning; he was not required to test-in or go through Basic but was accepted based on his already credible experience as an instructor pilot.

1942

Chris was instrumental in getting his brothers Henrik and Norman to enlist early on, saying to them, “you’ll end up a foot soldier if you wait“. He encouraged Dad to visit a recruitment pre-screen at the University Wyoming located in Laramie. Dad was inducted into the Civilian Pilot Training program (CPT) at Brees Field that September. Pilot trainees usually were required to solo after 11 hours of Dual instruction in the 65 h.p. Luscombe trainer. Dad achieved his 1st Solo flight after 8.2 hours and in 3 months time, completed his CPT with a checkride 8 November. His CPT Pilot Rating Book lists 28.2 hours of dual and 15 solo hours for a total of 43.2 TT.

1943

Dad reported to Navy Pre-flight School on the University of Iowa campus in Iowa City on January 21, 1943. Communications, theory of flight, gunnery, celestial navigation, aerology, aircraft recognition, engines and Naval history and traditions, with particular attention to Naval regulations. Physical training – calisthenics, swimming, basketball, soccer, football, gymnastics, wrestling, boxing, volleyball and hand-to-hand combat – was stressed throughout the training program. The pre-flight program was of 11 weeks duration.

“I wanted to join the Navy as an officer. My vision was 20-15” (exceptional) “…but the eye exam for color gave me trouble.” (a potential disqualification) He got hold of the Ishihara color charts used for testing and, “I memorized the chart!”. Dad loved athletics. He was in great physical shape having established a work ethic back home in Wyoming. Dad could handle a Fresno Plow behind a 4 horse team in a local gravel quarry. Having grown up in a competitive sense with his two brothers Chris and Norman, Dad was tops in Boxing and Wrestling among his Naval Cadets peers. “I was undefeated” save for an injury sustained when sparing with a fellow “bigger than I was and my leg got bent the wrong way. My knee was never the same again and even though while healing on crutches for a period of time, I was able to complete the routine… [for example] swimming the length of an Olympic sized pool underwater with one leg [trailing]. The rule was that in order to graduate, you had to stay with your class.”

Primary flight training for Cadets commenced at the Hutchinson Naval Air Station near Wichita with initial air work in Boeing Stearman N2S 3 bi-planes; known colloquially as the “Yellow Peril” from its overall-yellow paint scheme. Next came a checkout in the fixed gear but slightly more complex Vultee SNV-1 for the second phase of the training program.

“Vultee Vibrator.”

Successful candidates were transferred to a Texas air base in Corpus Christi where they practiced more advanced flying such as acrobatics in even more powerful aircraft. Other aircraft flown:

Naval Aircraft Factory N3N-3

North American SNJ-4

1944

Advanced training continued at the NAS Jacksonville (Cecil Field/Green Cove Springs) in Florida where they were introduced to the Douglas SBD -4 / -5 Dauntless, a scout plane and dive bomber. but it was the Grumman F6F Hellcat single-seat fighter / fighter-bomber aircraft, powered by a 2,000 hp Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10 Double Wasp radial that Dad would eventually fly on war missions and in battle combat. The base in Jacksonville simulated an aircraft carrier’s very short landing surface with overlay markings painted on the tarmac. It was the sawed off tree stumps no-mans land on the approach and departure overruns which “kept you honest”.

February: NAS Alameda (California)

His first training first flight in the F6F-3 was mid April after arriving at NAS Pasco Washington (Bombing Squadron 9) Other aircraft flown: FM-2 essentially a late production variant of the F4F Wildcat design but built by General Motors and Eastern Aircraft

September: “We progressed to San Ysidro’s Ream Field [Southern California] for the final phase of training “We also practiced on a landing surface actually floated on a special vessel made by Kaiser. We were required to make 3 consecutive (successful) landings” during final flight test evaluations. From the cockpit on an approach this area appeared impossibly small. A carrier used arresting cable gear to snag landing planes. On one of these practice ships, a new pilot botched his landing and crashed on the training carrier field, killing himself. “The rest of us that day were ordered to climb to 10,000 feet and circle in the area to wait for the wreckage to be cleared off.” The perspective view from that height exaggerated and seemed to multiply our doubts and undermine self confidence. That field was postage stamp size and it was do or die since at that stage of training the practice area was well off shore and thus beyond the fuel range for anyone to have thoughts of returning to the California coastline. Carrier Qualification was completed on September 13th in an F6F-5 using CVE-94 [escort class] USS Lunga Point

With ground and flight school complete we were sent from San Francisco to the Pacific theater via Pan American World Airways Martin Flying Boat with stops in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Guam, and finally Ulithi Atoll where we were assigned to the USS Yorktown CV-10. Dad recalls being cheated out of a birthday. By coincidental timing, “we crossed the International Date Line on the night before and lost a day.” Dad was 21 years old. (plus one)

Detached from the task force on 23 November Yorktown arrived back in Ulithi (staging anchorage) on 24 November. Dad joined his ship then (30 November)

“I was astonished to be in tropical waters. It was so warm. Growing up in Wyoming, I’d never experienced such wonder.” Otherwise there were few escapes from oppressive heat and humidity in the South Pacific. They were allowed the occasional swim which was followed by salt water showers. Sleeping below deck was near to impossible due to lack of refrigeration in those days. “I would come topside for air.” The artificial breeze from the ships forward movement offered relief. A carrier’s flat top upper deck also offered expansive space for exercise and calisthenics. “The vessel’s pitching made pushups very hard as you tried to extend your arms against it’s rise and fall.” There was an ice cream making machine onboard and “we ate extremely well – steak when you wanted.”

10 December, Yorktown put to sea again to rejoin Task Force 38. She rendezvoused with the other carriers on 13 December and began launching airstrikes on targets on the island of Luzon [Manilla] in preparation for the invasion of that island scheduled for the second week in January.

On 17 December, the task force began its retirement from the Luzon strikes. During that retirement, TF 38 steamed through the center of the famous typhoon of December 1944. He and another plane were among the last permitted to land aboard ship during the hurricane. The carrier deck was pitching so radically that there could be no more landing operations — for risk of damaging the ship. This meant that a small unfortunate remainder flew until fuel exhaustion and then went into the rough sea. Those were never heard from again.

The confused ocean had dramatic effect even on as large a ship as the Yorktown. The stern would rise and the propellers would cavitate “shaking the whole ship. The bow would dip down in a trough and the waves appeared higher than the flight deck – – 150 feet!”. That storm capsized and sank three destroyers—Spence, Hull, and Monaghan — and Yorktown participated in some of the rescue operations for the lone survivors of those three foundering ships.

The warship arrived back in Ulithi on 24 December. Yorktown fueled and provisioned at Ulithi until 30 December at which time she returned to sea to join TF 38 on strikes at targets in Formosa and the Philippines in support of the landings at Lingayen.

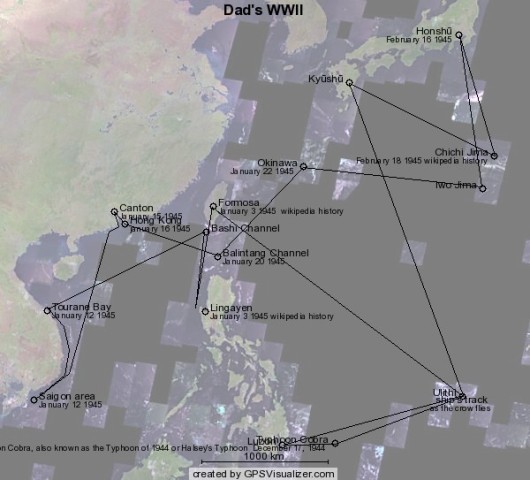

View Map Track of the Yorktown and Task Group 38 in the South Pacific from December 1944 until the end of Dad’s tour of duty – March 1945

It would seem that the more dangerous aspect or closest call would be during training or even routine logistics of fuel management and navigation. Getting lost and then running out of gas meant ditching into the sea where you might or might not be found and picked up before enemy or sharks got you. “They gave us ‘shark repellent‘ but I figured that this was more of a morale booster then effective. In flight school they told us to ALWAYS TRUST your flight instruments.” He would witness this at least once when experiencing disorienting vertigo while in cloud. “I was flying by the seat of my pants and you couldn’t see blue sky or ground for reference but, I glanced at my instruments and noticed that my airspeed was high and altimeter unwinding.” Luckily he came to the (correct) conclusion that he was headed for disaster and arrested the descent and resumed climb. He and his wingman had become lost. They had been assigned to fly vectors issued over radio by a radar controller aboard a fleet destroyer. The controller would scan his scope for Bogeys, which could be potential Kamikaze, and then would dispatch the pair to intercept. After many heading changes Dad’s flight of two lost awareness of their precise position having been relying on their controller for guidance. But the radio controller soon lost touch with them as he vectored them to and fro – beyond transmitter signal coverage. With the need for self help they decided to try and get above the clouds to get their bearings. Out of ideas, his “wingman made visual signal motions to me that ‘you’ve got it’. I took the lead and from on top we were keen to hear the single navigation beacon from our carrier that would return us home. We were really low on fuel by now flying box patterns to try and pick up that signal. Straining for that familiar morse code signal we finally located our ship. Not wanting to approach from such a high altitude and be mistaken for enemy ourselves we descended promptly to just above sea level and by miracle our carrier was steering into the wind and receiving the last arrivals. My wingman and I just joined the landing pattern and safely arrived as though nothing had ever happened. We were lucky.” If a carrier perceived danger or suspended landing operations stragglers where asked to ditch alongside and they would be picked up (hopefully).

1945

“We saw airborne action raids over Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and over Formosan airfields where we shot our rockets at enemy aircraft as they sat imobile on the ground and encountered some of the fiercest defense in the form of return fire. The sky blackened with flak and tracers seemed to came right at us. It was the bullets that I COULDN’T see that I thought about.”

The carriers began with raids on airfields on 3 January on the island of Formosa and continued with various targets for the next week. On 10 January, Yorktown and the rest of TF 38 entered the South China Sea via Bashi Channel to begin a series of raids on Japan’s inner defenses. On 12 January, her planes visited the vicinity of Saigon and Tourane Bay, Indochina, in hopes of catching major units of the Japanese fleet. Though foiled in their primary desire, TF 38 aviators still managed to rack up a stupendous score—44 enemy ships, of which 15 were combatants. On 15 January raids were launched on Formosa and Canton in China. The following day, her aviators struck at Canton again also went to Hong Kong. “We came upon a solitary boat” west of Formosa which he described as a ‘chinese junk ‘ This heavy timbered vessel seem to absorb any damage from their 50 caliber machine guns by refusing to sink as he and his buddies (8 planes) made numerous strafing runs upon it. “I didn’t know if there was anyone on it but felt sorry for them if there were.” You might think this the cat toying with the mouse but the enemy was resourceful and used any and everything to try and take us out. As an example, the derelict hull of a vessel previously out of commission and half sunk in shallow water turned up with impromptu anti-aircraft gun emplacements one day. This the flyers realized when startled to see enemy tracer fire emanate from the wrecked hulk and spent “rounds striking the sea just shy of my position.”

On 20 January Yorktown exited the South China Sea with TF 38 via Balintang Channel. She participated in a raid on Formosa on 21 January and another on Okinawa on 22 January before clearing the area for Ulithi.

Read an: After Action Report - (Source)

“We’d generally fly low on the water, to avoid enemy detection. When an island appeared, we would climb slightly so as to just pop over and clear the obstacle. On one such hop after a bombing run, I found myself directly overhead an enemy gun emplacement. Quite a nest of guns actually; and it was a little hair raising to be staring down barrels of these cannon as I saw the enemy ground crew struggle to swing to and get a bead on me. But my sudden appearance had surprised them as much as it had surprised me. I was the first to fire a burst from my 50 caliber machine guns as I passed and lucky for me I saw them briefly cower which delayed their retaliation and they never got off a shot in time. I’d have been blown to bits otherwise.”

On the morning of 26 January, Yorktown re-entered Ulithi lagoon with TF 38. She remained at Ulithi arming, provisioning, and conducting upkeep until 10 February. At that time, she sortied with TF 58, the 3rd Fleet becoming the 5th Fleet when Spruance relieved Halsey, on a series of raids on the Japanese and thence to support the assault on and occupation of Iwo Jima.

An advantage for the military pilot was that he never really saw the enemy eye to eye. “We carried a single 500lb bomb or a Napalm bomb, and 6 rockets distributed 3 on each wing. We were given flight missions to carry out and we did them. Some guys were afraid and would abort and return and or not even launch feigning perceived engine or mechanical trouble.” Dad was proud to report that during the length of his tour that he “flew more missions than anyone in his air group except for one other guy.”

On the morning of 16 February, the carrier began launching strikes on the Tokyo area of Honshu. On 17 February, she repeated those strikes before heading toward the Bonins. Her aviators bombed and strafed installations on Chichi Jima on 18 February. The landings on Iwo Jima went forward on 19 February, and Yorktown aircraft began support missions over the island on 20 February. Those missions continued until 23 February at which time Yorktown cleared the Bonins to resume strikes on Japan proper. She arrived at the launch point on 25 February and sent two raids aloft to bomb and strafe airfields in the vicinity of Tokyo.

Dad’s Air Group #3 was one of the first wave of US planes to go over mainland Japan. It was here that Dad engaged in air to air fighting (only once) he and a wingman were on the receiving end of a dogfight with a Japanese Zero [the Mitsubishi Zero’s had extraordinary maneuverability] . They both tried climbing at full power while trying to pursue. “We were ‘hanging on the prop’ (near stall speed) but the Zero was lighter and always still right there just above our gun sights at which point he kicked his rudder and came back down at us.” The Japanese pilot had a shot and “hit my wingman, who went down. When I returned to the Yorktown I learned that my wingman had landed in the sea and was picked up.”

On 26 February, Yorktown air crewmen conducted a single sweep of installations on Kyushu before TG 58.4 began its retirement to Ulithi. Yorktown re-entered the anchorage at Ulithi on 1 March. She remained in the anchorage for about two weeks. At this point Dad’s tour came to a close. His flight log book entry on the 9th of March 1945 states ‘Going home’

He and other veterans left his ship for the United States via the USS Lexington CV-16 (bound for a Puget Sound overhaul). On the 10 day return journey they visited Guam “with orders to stay out of the jungle because of enemy hold outs” keen on perpetuating the war. By policy, naval pilots served in combat for a finite tour (e.g. 250 combat hours, or six months, or 25 missions whichever came first). Then they rotated home, typically to train other pilots.

He was assigned to VBF-97 air squadron at NAS Gross Ile (Michigan) that spring continuing to fly VF aircraft including the Vought F4U-1D Corsair and then was detached to the Naval Photographic Reconnaissance Training School (Squadron Two) at the Naval Air Facility in New Cumberland (Harrisburg, PA) . Through the summer Dad became qualified for combat photography and photographic intelligence with the F6F-3P, a photo reconnaissance conversion with one camera in the rear fuselage just behind the wing.

In September he traveled back to the West Coast reassigned by CASU-50 [NAS Seattle] to Pasco Washington to await the reforming of Fighting Squadron 12.

October: Reim Field [San Diego] Other aircraft flown there: Beechcraft Staggerwing GB-2, and the NE-1 — the Navy version of the civilian Piper ‘Cub’. In fact, according to the logbook, Mom! was Dad’s passenger in NE-1 [49340] on a joy flight from the Burbank airport on November 4th.

Dad’s last F6F-5 flight logged was a 2.0 hr search mission across the border into Mexico on December 28, 1945. Final flight made (TBM cross-country) was on January 7, 1946. He’d logged 793.5 naval flying hours for a grand total of 836.7 TT with 48 actual carrier landings.

Decoration Medals and Awards:

- Air Medal

- American Area

- Asiatic-Pacific Area ( 2 Stars )

- Philippine Liberation ( 1 Star )

- World War II Victory

(“Felix the Cat” )

Air Group Three (CAG 3 aka Group 3) was one of the Carrier Air Groups attached to the USS Yorktown (CV-10) Air Group Three was attached to the USS Yorktown from October 24, 1944, through March 1945.

A carrier air group is made up of three parts, a fighter squadron (VF-3 aka Fighting 3), a bombing squadron (VB-3), and a torpedo squadron. (VT-3). Source

Roster of Officers VF3 dated 15 MARCH 1945

Reconstructed Route Trace of the USS Yorktown during Dad’s Tour

Chris Strombotne

Uncle Chris, while stationed stateside at the Los Alamitos Navy Training Field in 1943, lost his life in an accident. He and his student in one aircraft touched wings or otherwise collided with a similar aircraft during a naval flight formation training exercise.

Chris Erik Strombotne (1921-1943)

Norman Strombotne

Uncle Norman’s plane, badly shot up (aimed Flak), went down in Northern Italy. They had to bail out because of mountainous terrain; a landing was not possible. Norman said that they “parachuted into a massive snow bank and that by the time they had extricated themselves enemy soldiers were there to greet them — rifles pointed”. He was interned for the duration in a German POW camp. Stalag Luft I in Barth, Germany. North 3 – Barracks 9 (Block 309) Room 6.

There is a reconstructed narrative based on Lt. John E Thompson’s P.O.W. diary. He details his journey to the internment camp, time spent there and Uncle Norman’s was likely a carbon copy. Norman is mentioned by name. See the excerpt below.

Following advanced Navigational training at ANS San Marcus, Texas, Uncle Norman was assigned to the 415th Squadron operating the Consolidated B-24 Liberator. He flew combat missions from Lecce Airfield, Italy as part of the 98th Bombardment Group. Uncle Norman flew in a number of sorties, which are listed. Most of these records were methodically type written documentation. The period Nov 12 to Dec 21 however is vague. Those narratives do not list the crews and they were not transcribed.

- Nov 05 Vienna Florisdorf Oil Ref., Austria

- Nov 07 1944 Mezzacorona RR Bridge, Italy

- Nov 08 1944 Vienna/Schwechat Oil Refinery, Austria

- Nov 12 1944 Avisio Viaduct, Italy

- Dec 21 1944 Rosenheim Marshalling Yards, Germany

- Dec 29 1944 Brenner Pass Rail Loop, Italy (final mission)

- Dec 29 1944 @ 13:30 hrs. Cortina d’Ampezzo, Sillian District of Lienz

- Jan 04 1945 temp transfer to Dulag Luft Oberursel and or Wetzlar

Brenner Pass is a mountain pass through the Alps along the border between Italy and Austria. It is the lowest of the Alpine passes, and one of the strategic importance in the area. The 29 December 1944 heavy bombardment mission, was his last as they were shot down this date. The best we can piece together is that the aircraft suffered damage from Flak after having reached the heavily defended target. Hearsay info puts the aircraft shot down near Vipiteno (Fundres (Pfunders) in the Italian province of South Tyrol (Süditrol)) just below the Austrian border.

The Missing Air Crew Report (MACR 11089) shows the departure from Fortunato Cesare Aerodrome, Lecce, Italy at 08:30 with a course axis of attack of 038 degrees. Its last known position was 46°52’N 11°45’E 29 DEC 1944 @ 13:10 hrs. local time. The weather was CAVU and the [mission report] documented visual sighting of: prop feathered after target on the ill fated bomber. A radio distress transmission from 860B was received by two other planes in area. There were 11 crewmembers aboard. All were POW for the duration and RTD at war’s end.

Excerpt from the Autobiography by John Edward Thompson, M.D.

The next day with several other airmen that they had captured, we were taken in a truck to Verona in northern Italy. Verona was an assembly point for prisons of war. Two elderly soldiers, who were going home on leave, were assigned to take us to Frankfurt, Germany for all Air Force officers were sent to the Lutwaffe Interrogation Center in that city. The highway and railroads which go northward from Italy pass through an opening in the mountains called Brenner Pass, and from there you go on into Austria and southern Germany. This was a very dangerous and difficult part of our journey because the Brenner Pass was being constantly bombed to shutdown the highways and railroads. All of the war supplies that went into Italy came down this system of roads. I remember walking through snow, riding street cars, hitch-hiking, trains, cars, buses, and any kind of transportation that these two older soldiers could provide us to get us into Germany. I remember being in a town which I believe was Trento in Italy. We got off a train late in the evening and we were cold and tired. The German soldiers took the four of us into a building that looked like it could be a gymnasium of a school. Four airmen in a room with a hundred German soldiers was a scary situation. We stuck very close to our two guards and stayed in the dark shadows as much as possible. We did get a bowl of hot soup and a piece of bread that evening which tasted very good because we were cold, wet, and frightened. We arrived at Bolzano in the later part of the morning on the 2nd of January, and after resting for six or seven hours, we took a night train because it was safer to travel at night. There are now 22 airmen in the prisoner group including Hopkins and Essenberg and the three of us became room-mates at Barth. On the third of January we experienced three air alerts, and most of the day the train stayed in a little town waiting for the protecting darkness. Then we passed through Innsbruck, Rosenheim, and into Munich. Next cities were Augsburg, Stuttgart, and finally we pulled into Frankfurt in the early morning hours on the fifth of January. In the railroad station at Frankfurt we again experienced a night air raid, we were kept on the train; fortunately none of the bombs came close to us although we could hear them. In the morning we were taken to Oberusel which was the Interrogation Center. We were happy to get out of Frankfurt because this was a primary bombing target for both the British and American Air forces.

Oberusel was about five miles north west of Frankfurt, and when we arrived there we were immediately placed in solitary confinement. The tiny room contained a small cot, the room had a single small window at the upper part of the outer wall, the door had a small opening through which the guards could place some food or water. In the corner of the room there was a bucket for a toilet. We were nervous and uncertain of the future; we had been traveling for a week in unheated railroad cars, hungry and tired with little sleep. Solitary confinement was used as a form of mental torture to make the prisoner talk; physical torture was never reported by any prisoner in Oberusel.

In the morning a small breakfast of bread and coffee was placed in the door opening. Following this I was taken to the interrogation room by a German guard, and the door was closed behind me. I remember entering this room with suspicion and anxiety. Behind the desk sat a German officer in a blue uniform, I didn’t know what his rank was but I think it was Mr. Hans Scharff who was the noncommissioned officer whose specialty was interviewing fighter pilots. Questions were asked and I answered with only my name, rank, and serial number. For this is all that is required by the Geneva Rules of War. He then offered me a cup of coffee and a cigarette and asked about my health, how I was doing, sorry that they had to place me in solitary confinement. He did this in quite a pleasant way. He spoke perfect English because he had been a business man in South Africa, and while returning to Germany the war started and he was drafted into the military. Since I appeared to be uncooperative, he sent me back into solitary confinement; another evening in this dark room, cold and miserable. The next morning the same events happened. You were taken into a warm pleasant room with carpeting, and there behind the desk was Mr. Scharff. He again offered me a cigarette and coffee, and ordered his secretary to find a file on Lt. Thompson. He tried to impress me with the fact that the file on the 86th Fighter Group had my name in it, and this was easy for him to identify my group because the airplane had the group’s markings on it, and he knew what group I belonged to and where I was stationed. He again asked some very simple questions about where I was from, and where I was born, and he showed me the file, and it even had the date of my graduation from flight school at Moore Field. He only seemed to be interested in one thing, and that was a group of pilots from Brazil had come to the air field at Pisa in December, and he seemed to lack information about them. It was obvious that I did not have much information for him, and he then thanked me and said I was going to be moved to the transient camp at Wetzlar. This was managed by the Swiss Red Cross to protect the prisoner of war with warm clothing and we got our first hot meal there which included potatoes, fish, cocoa, and two slices of bread. On the ninth of January we left Wetzlar on a train, and my diary stated that there were 80 men in the railroad car, and there were ten cars in the train. On the 11th we were again bombed in the railroads yards in the city of Wittenburg; fortunately none of the bombs struck our train car. We passed through Berlin safely and arrived at ten o’clock in the morning on the 12th of January at Stalag Luft Number One which was situated only one mile from the Baltic Sea. For any historian who would like to know more about this interrogation center and the techniques that were used there to obtain the information that the Luftwaffe wanted, you should read the June 1976 issue of the Air Force magazine which has a very complete article on Mr. Scharff. Also read a book that is called Nazi Interrogator. Mr. Hans Scharff, by Raymond Toliver. One can appreciate the difference between the professional German soldier and the Nazi criminals that terrorized Europe.

The prison camp was a dreary looking place with the double row of ten foot high, barbed-wire fence with coils of additional barbed-wire on the ground, and a warning wire beyond which the guards shoot. At intervals along the fence were wooden watch towers with powerful search lights to guard against night escapes. The warning wire was about knee high and everyone kept their distance from it. The entire camp, including the administrative buildings, was surrounded by a second such double fence. Our barracks was two feet above the ground to allow the German police dogs to sniff around underneath the building, and they were allowed to roam in the compound at night. Each barracks had a central corridor with small rooms on either side. There were ten rooms in the barracks, twenty-four men to a room, and there were nine barracks in each compound so that there was essentially about two thousand men in an area which was 175 yards square. We slept on wood slab bunks with a mattress filled with paper or wood shavings. Heat was supplied by a small iron stove and it failed to keep us warm in the harsh Baltic winter. Each of the barracks had a night latrine and cold water. One meal a day was served from the kitchen and usually was a soup made with turnips or potatoes. There was an occasional addition to the soup of horse meat. Important were the Red Cross food parcels, but these were few in number due to transportation difficulties so the prisoners lived on the edge of starvation.

Medical treatment was minimal and provided by a small staff of British doctors who had been captured in the war in battles like Dunkirk. To occupy our time the Red Cross provided us a small library and we even had some textbooks on various sciences. We had educated people in the camp who provided lessons in languages such as German and Italian. I took a series of lectures on Physics and Mathematics and we occupied our time with serious types of discussions. We took our uniforms apart and sewed them back together. We practiced Kriege Kraft and made many things out of tin can strips. I learned to play bridge from Bill Reichert and this helped to pass the days without wasting our energy. We wrote poetry, drew pictures, and thought of food almost every waking minute. On April 18th I sold all my future Red Cross prunes to Pat Murphy; he paid me by a check written in a camel package wrapper which , cashed after the war. The one box of prunes cost Pat 50 dollars. Showers were infrequent, and clothes washing was rare because the weather was cold and we only had one uniform. Lice and Scabies were always a constant threat. There had been stories and movies written about the great escapes from prison camps in World War II but, as far as I know, no one ever managed to tunnel out of Stalag Luft One.

By the time I reached prison camp, our commanding officer sent out a directive that no one was to try to escape, the risk was too great, and the war was soon to end. The standard of exchange were cigarettes and the chocolate “D Bar”. The “D Bar” had the greater value because it represented food, and the exchange often would get you ten to twenty packs of cigarettes for one chocolate “D Baril. I had two items that Germans did not take away from me when I became a prisoner, one was a watch and the other was a cigarette lighter of a catalytic type. I had been offered as much as one hundred packs of cigarettes for it, and of course with that many cigarettes I could buy wine or food although the German guard would be severely penalized if he was caught. I did manage to get a bottle of cigarette lighter fluid from a German guard for a pack of cigarettes and I thought this would work in my catalytic lighter. When I first put this fluid into it, it melted the plastic lighter and there went my most valuable asset I had in prison camp.

From my home town I would meet Walt Wenger at church services on each Sunday morning whenever we were allowed to go to church. Walt was the brother-in-law to my brother Paul and he had been there for a year and had news from home. We received news reports from both the British and the German radio and we even had a small news letter that was published each day and posted in the barracks.

I kept a small diary and these are some of my notes. “ Rations are small, the Red Cross boxes are not coming through. Hungry all the time. Camp is filling up quickly with more prisoners coming in each day. Wet, mild weather is creating mud. Irv Smirnoff moved from our room. We worry for Irv is of the Jewish faith. Paul Anderson has a unique story. He was a ground group engineer, and went on tour of Berlin with a pilot friend. He was shot down on his first and only mission. No shower for three weeks. Crabs seem to be spreading throughout camp.” Note says on the seventh of February, “Perrot has Scabies. Air raid alarms are occurring. Do not look out the window during an air raid because the German police dogs are roaming around and will attack through the window. Electricity is short. Made a bet with Ray Kader on the 19th of February as to when the war was going to be over.” I made a resolution that when I first stepped foot on soil in the United States I was to pray to God and give thanks. With the Russian army drawing near we were in danger; we realized that in our weak condition we might not be able to tolerate a long march. Search parties by the German guards were still common. To pass the time we studied and had classes in Mathematics and German. For Easter on the 1st of April we got some food parcels and stuffed ourselves with rather rich food. Many got sick with vomiting and diarrhea. On the 4th of April Max Schmeling visited our camp in his role of public relations expert for the German government; they realized that the future of Germany depended on a close relationship with the United States and it showed the fear that the Germans had for the Russians. We lost our classroom because more P.O.W.s needed the space to live in.

Seventeenth of April I made contract with Murphy for fifty dollars. Sold all my future “D Bars” to him. Nineteenth of April we heard artillery, which we felt was due to the Russian army. Later part of April the food supply seemed to increase and everybody had more to eat. On the 28th of April Russians broke out of Stettin and were coming towards the prison camp. Thirtieth of April we dug slit trenches in case the war broke out in our area.

On the first of May we awakened at one-thirty in the morning to find that we were free. The Germans guards had left the camp during the night to fight against the Russian army. Col. Zemke gave order to restrict our activities to the camp. In the evening, a Russian tank came up to the compound and we were all surprised to see the first soldier to come out of the tank was a blond woman. Ray Kader and two other P.O.W.s and I went to Barth where we met the Russian army. On a Baltic sandy beach, we saw a gruesome sight that brought home the horrors of war. On the beach there was a table cloth spread out with some containers of food, and around this there were two small children, one in a baby carriage, and three other women. All were dead with a single bullet hole in their heads. Ray says that we buried them, but my notes do not describe that part, and I often wonder if anyone ever identified them or knew about them. The Russian had the guns and they did all the talking, and sometimes we wondered about being a Russian hostage. The Russians did furnish us meat after they swept the entire country side and took all of the cattle from the farmers. We visited the German air field and I brought home some souvenirs from a Luftwaffe officer’s room. I still use them today when I talk to school children about veterans, need for patriotism, and respect for the flag. One afternoon we had the opportunity to see a Russian U.S.O. type of show with singing, and dancing.

War officially ended at midnight on the eighth of May. On the ninth, my note says, Abbott, Yellot, Strombotne, and I ate breakfast with several Russian soldiers, and we had a light lunch with a couple of Germans. In the evening we had supper with the Americans. So this was an international day. We left Barth on the 13th aboard the B.17s of the Eighth Air Force and we were glad to leave because we had developed a fear of the Russians. Most of the P.O.W.s sat on the floor of the airplane. I probably was the smallest and I ended up in the tail gunner seat. In the flight back to France, I became quite nauseated due to vertigo. The next day we flew to Le Havre in C47’s and were placed in a resettlement area called Camp Lucky Strike. There we received a shower, new clothes, Typhus shot, and I remember being sprayed with D.D.T. to control any lice or crabs. We stayed at Camp Lucky Strike for one week seeing movies, eating, and getting our strength. One of my notes said we got into the town of Nettefleur where we had a few beers. Soon we were all discouraged because the camp was disorganized and on the 21st Anderson, Troy, Kader, Essenberg, and I decided to skip out of camp and travel to Paris. There we processed in at the P.O.W. center and were giving officers uniforms and 125 dollars in cash. That night Troy and I went to the Bel Tabarin night club. Troy and I were buying champagne for everybody, and we had a really great time. Troy and I then caught a train to Dijon in France to visit with Troy’s friends of the 17th Bomb Group.

His fellow pilots treated us like royalty with steak, best of wines, and anything that our hearts desired. On the 26th we left Dijon in a jeep with one of Troy’s officer friends and he drove us back to Camp Lucky Strike. There I met my good friend Joe Dell, who had been in training with me and he had also become a prisoner of war when he had to bail out of his P-47 airplane over southern Germany. Confusion persisted and on the 2nd of June Abbott and I caught a ride on a B-17 to Ipswich in England and landed at the 100 Bomb Group Air Base. In London we stayed at the Red Cross center and on the 4th we took a train to Blackpool where the English people welcomed the two Ex. P.O.W.s. With our money almost gone, we again checked in at the Air Force center and were given orders to proceed to Southampton where we were processed on the 12th. On the 13th we boarded a hospital ship. Most of the passengers where wounded infantry soldiers and we had good food and pleasant company. We arrived in the harbor in New York on the 12th of June, and I remember with pride and thankfulness to see the Statue of Liberty. When the ship docked, we were welcomed by bands and reception committees. As we stepped ashore happiness was overwhelming with the realization that we were really, really back in the United States of America.

picture credit: 860 “Paper Doll”

15th Air Force / 98th Bomb Group / 415th Bomb Squadron [ link ] The black/yellow stripes for the 98th BG is their tail code marking. The RCL (recall code) was “B” painted in red.

2nd Lt. Norman J. Strombotne was recognized for his participation in the Northern Apennines Campaign. He was awarded: